When we wish to assess the performance of a business, we’re looking for ways to measure the financial and economic consequences of past management decisions that shaped investments, operations, and financing over time. The important questions to be answered are whether all resources were used effectively, whether the profitability of the business met or even exceeded expectations, and whether financing choices were made prudently. Shareholder value creation ultimately re- quires positive results in all these areas which will bring about favorable cash flow patterns exceeding the company’s cost of capital.

As we’ll see, there is a wide range of choices among many individual ratios and measures, some purely financial and some economic. No one ratio or measure can be considered predominant. We’ll demonstrate primarily the analysis of business performance based on published financial statements. These represent the most common data source available for the purpose, even though they are not designed to reflect economic results and conditions. We’ll also discuss the more important measures that help assess economic performance aspects. Our focus will be on key relationships and indicators that allow the analyst to assess past performance and also to project assumed future results. We’ll point out their meaning as well as the limitations inherent in them. In the final we’ll discuss the larger context of valuing a company or its parts in economic terms, a process that is based on an intense assessment of performance drivers and strategic positioning, and that requires developing expected cash flow results for which past performance is only a starting point.

Because there are so many tools for doing performance assessment, we must re- member that different techniques address measurement in very specific and often narrowly defined ways. One can be tempted to “run all the numbers,” particularly given the speed and ease of computer spreadsheets. Yet normally, only a few selected relationships will yield information the analyst really needs for useful insights and decision support. By definition, a ratio can relate any magnitude to any other; the choices are limited only by the imagination. To be useful, both the meaning and the limitations of the ratio chosen have to be understood. Before be- ginning any task, therefore, the analyst must define the following elements:

Any particular ratio or measure is useful only in relation to the viewpoint taken and the specific objectives of the analysis. When there is such a match, the measure can become a standard for comparison. Moreover, ratios are not absolute criteria: They serve best when used in selected combinations to point out changes in financial conditions or operating performance over several periods and as com- pared to similar businesses. Ratios help illustrate the trends and patterns of such changes, which, in turn, might indicate to the analyst the risks and opportunities for the business under review.

A further caution: Performance assessment via financial statement analysis is based on past data and conditions from which it might be difficult to extrapolate future expectations. Yet, any decisions to be made as a result of such performance assessment can affect only the future—the past is gone, or sunk, as an economist would call it.

No attempt to assess business performance can provide firm answers. Any insights gained will be relative, because business and operating conditions vary so much from company to company and industry to industry. Comparisons and standards based on past performance are especially difficult to interpret in large, multi business companies and conglomerates, where specific information by individual lines of business is normally limited. Accounting adjustments of various types present further complications. To deal with all these aspects in detail is far beyond the scope of this book, although we’ll point out the key items. The reader should strive to become aware of these issues and always be cautious in using financial data.

To provide a coherent structure for the many ratios and measures involved, the discussion will be built around three major viewpoints of financial performance analysis. While there are many different individuals and groups interested in the success or failure of a given business, the most important are:

Closest to the business on a day-to-day basis, but also responsible for its long-range performance, is the management of the organization, whether its members are professional managers or owner/managers. Managers are responsible and accountable for operating efficiency, the effective deployment of capital, useful human effort, appropriate use of other resources, and current and long-term results—all within the context of sound business strategies.

Next are the various owners of the business, who are especially interested in the current and long-term returns on their equity investment. They usually expect growing earnings, cash flows, and dividends, which in combination will bring about growth in the economic value of their “stake.” They are affected by the way a company’s earnings are used and distributed, and by the relative value of their shares within the general movement of the security markets.

Finally, there are the providers of “other people’s money,” lenders and creditors who extend funds to the business for various lengths of time. They are mainly concerned about the company’s liquidity and cash flows that affect its ability to make the interest payments due them and eventually to repay the principal. They’ll also be concerned about the degree of financial leverage employed, and the availability of specific residual asset values that will give them a margin of protection against their risk.

Other groups such as employees, government, and society have, of course, specific objectives of their own—the business’ ability to pay wages, the stability of employment, the reliability of tax payments, and the financial wherewithal to meet various social and environmental obligations. Financial performance indica- tors are useful to these groups in combination with a variety of other data.

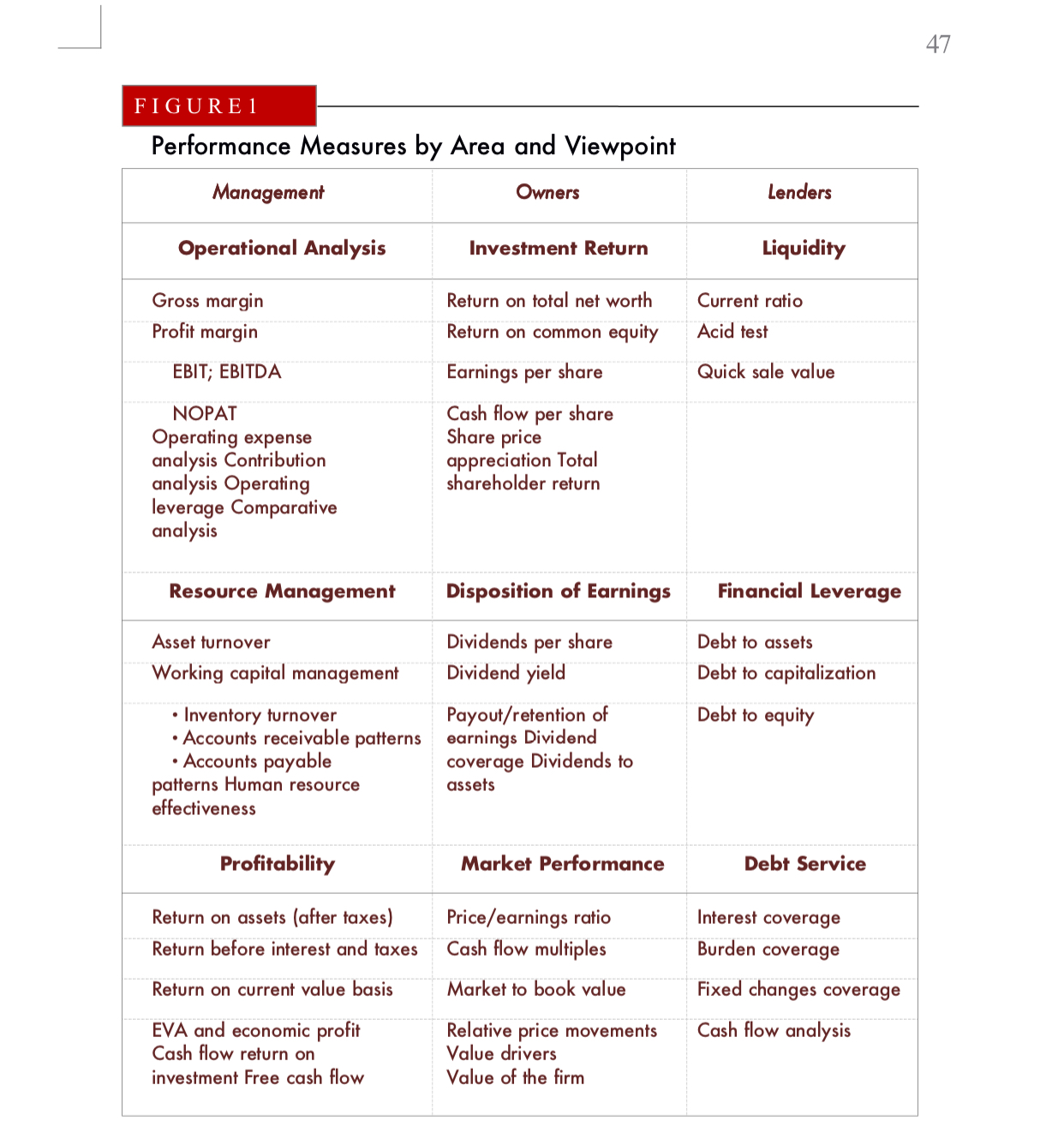

The principal financial performance areas of interest to management, owners, and lenders are shown in Figure below , along with the most common ratios and measures relevant to these areas. We’ll follow the sequence shown in the figure and discuss each subgrouping within the three broad viewpoints. Later, we’ll re- late the key measures to each other in a systems context.

Management has a dual interest in the analysis of financial performance: