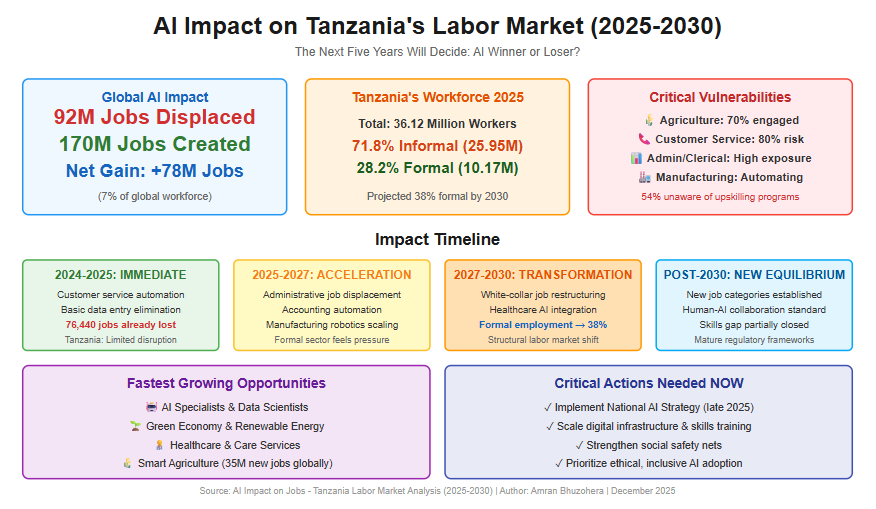

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is rapidly reshaping the global world of work, redefining how jobs are created, performed, and displaced. Between 2025 and 2030, AI-driven automation and digital transformation are expected to disrupt labour markets at a scale comparable to past industrial revolutions, but at unprecedented speed. According to the World Economic Forum, while AI and related technologies are projected to displace approximately 92 million jobs globally, they are also expected to create 170 million new jobs, resulting in a net global job gain of about 78 million positions, equivalent to roughly 7% of the current global workforce. However, these gains will not be evenly distributed across countries, sectors, or skills levels.

For Tanzania, the implications of this transformation are particularly profound. The country enters the AI era with a labour market that is structurally vulnerable yet full of latent opportunity. As of 2025, about 71.8% of Tanzania’s workforce—approximately 25.95 million people—operates in the informal sector, characterised by low job security, limited social protection, and minimal access to upskilling opportunities. Only 28.2% of workers (10.17 million) are in formal employment, although projections suggest gradual formalisation could raise this figure to around 38% by 2030 if supportive policies are implemented.

Globally, evidence shows that AI-related job displacement is no longer a future risk but a present reality. By 2025 alone, an estimated 76,440 jobs had already been eliminated worldwide due to AI adoption, with occupations such as customer service, data entry, retail cashiers, and clerical work experiencing the earliest impacts. Studies from the St. Louis Federal Reserve further demonstrate a strong positive correlation (0.47) between AI exposure and rising unemployment in highly digitised occupations between 2022 and 2025, particularly in computer and mathematical roles. These trends signal what lies ahead for emerging economies like Tanzania as AI adoption deepens.

Sectoral exposure in Tanzania mirrors global patterns but is intensified by the country’s economic structure. Agriculture employs roughly 28% of the national workforce and engages nearly 70% of Tanzanians indirectly, making it the backbone of livelihoods. While AI-powered precision farming, automated irrigation, drone-based crop monitoring, and pest-prediction systems promise productivity gains and climate resilience, they also reduce demand for manual labour. Without proactive reskilling and value-chain upgrading, technological efficiency gains could translate into rural job losses rather than inclusive growth.

Other vulnerable sectors include manufacturing and SMEs, where manual procurement, inventory management, and quality control are increasingly being automated; customer service and call centres, facing automation risks of up to 80% by 2025 due to chatbots and virtual assistants; and administrative and clerical roles, where bookkeeping, data entry, and document processing are rapidly being replaced by AI systems. Financial services are also transforming through AI-based credit scoring, fraud detection, and risk assessment, reducing demand for entry-level professionals while increasing demand for advanced digital skills.

At the same time, AI is creating new growth pathways. Globally, the fastest-growing roles between 2025 and 2030 include AI specialists, data scientists, software developers, cybersecurity analysts, and AI ethics officers, alongside strong employment growth in the green economy and care sectors. Notably, agriculture, construction, education, and healthcare are expected to generate the largest absolute number of new jobs, driven by population growth, infrastructure expansion, and social service needs. For Tanzania, this presents a strategic opportunity to align its youthful population, agricultural base, and digital transformation agenda with future-ready skills development.

Tanzania has begun laying the foundations for this transition. Key initiatives include the development of a National AI Strategy (expected in late 2025), the establishment of AI research labs through collaborations between the University of Dodoma and NM-AIST, the Digital Tanzania Project, and sector-specific programmes such as AI4D Agriculture, supported by international partners. However, major constraints remain, including limited digital infrastructure, unreliable electricity, a critical shortage of AI professionals, fragmented regulation, and low awareness—evidenced by the fact that 54% of workers are unaware of formalisation or digital upskilling programmes.

Ultimately, the period 2025–2030 will be decisive. AI will not simply determine how many jobs exist in Tanzania, but what kind of jobs, who gets them, and under what conditions. Without timely policy action, the AI transition risks deepening informality, widening rural-urban and gender inequalities, and marginalising low-skilled workers. With deliberate, inclusive, and well-sequenced reforms—focused on digital infrastructure, mass skills development, ethical AI governance, and social protection—Tanzania can instead leverage AI as a catalyst for productivity, formalisation, and sustainable development. The challenge is not whether AI will transform Tanzania’s labour market, but whether the country will shape that transformation proactively or react to it too late.

Artificial Intelligence is poised to fundamentally transform the global job market by 2030, and Tanzania will not be exempt from these changes. While AI will displace millions of jobs worldwide, it will also create new opportunities, resulting in a net positive job growth. However, the transition period will require significant workforce adaptation, particularly in Tanzania where 71.8% of the workforce operates in the informal sector.

The next five years will be decisive for Tanzania’s position in the age of Artificial Intelligence. AI is no longer a distant or abstract technology—it is already reshaping jobs, skills, and productivity across the global economy. For Tanzania, the stakes are exceptionally high. With over 70 percent of the workforce operating in the informal sector and a large share of livelihoods concentrated in agriculture and low-skilled services, the country faces both significant exposure to AI-driven disruption and a rare opportunity to leapfrog into a more productive, formal, and resilient economic structure.

Whether Tanzania emerges as an AI winner or loser will not be determined by technology alone, but by policy choices, investment priorities, and the speed of institutional response. If AI adoption advances without parallel investments in digital infrastructure, skills development, and worker protection, the result is likely to be deeper informality, rising job insecurity, and widening inequalities between urban and rural areas, formal and informal workers, and skilled and low-skilled populations. In such a scenario, productivity gains would accrue to a narrow segment of firms and workers, while the majority remain excluded from the benefits of technological progress.

Conversely, Tanzania has a credible pathway to becoming an AI winner. Ongoing initiatives—such as the development of a National AI Strategy, expansion of digital infrastructure, investment in AI research and education, and pilot applications in agriculture, healthcare, education, and finance—provide a foundation upon which inclusive AI adoption can be built. If these efforts are accelerated and aligned with large-scale upskilling, formalization incentives for SMEs, ethical AI governance, and targeted support for vulnerable groups such as youth, women, and rural workers, AI can become a driver of productivity, decent work, and sustainable growth.

Crucially, the transition period between 2025 and 2030 will be the most disruptive. Decisions taken now will determine whether Tanzanian workers are displaced by automation or empowered to work alongside AI technologies. This window demands urgency: scaling digital literacy, embedding AI skills across education and vocational training, strengthening social protection systems, and ensuring that AI adoption serves national development goals rather than undermines them.

In the end, Tanzania’s AI future is not preordained. The country can either react to AI-driven change after jobs are lost and inequalities widen, or act decisively to shape a human-centered, inclusive AI economy. The next five years will answer the question clearly. With deliberate, coordinated, and inclusive action, Tanzania can position itself as an AI winner. Without it, the cost of delay will be measured not only in lost jobs, but in lost development potential. Read More of this Topic: Doing Business in Tanzania 2025-2030

| Metric | Figure | Source |

| Jobs Displaced Globally | 92 million | World Economic Forum 2025 |

| New Jobs Created Globally | 170 million | World Economic Forum 2025 |

| Net Job Gain | +78 million (7% of global workforce) | World Economic Forum 2025 |

| Jobs Already Displaced (2025) | 76,440 positions | SSRN Research 2025 |

| Businesses Transforming with AI | 86% by 2030 | World Economic Forum 2025 |

| Organization | Jobs at Risk | Timeline | Notes |

| McKinsey Global Institute | 800 million jobs | By 2030 | Global automation impact |

| Goldman Sachs | 300 million full-time jobs | Long-term | Equivalent positions worldwide |

| World Economic Forum | 85 million jobs | By 2025 | Earlier projection |

| PwC | 30% of US jobs | By 2030 | Subject to automation |

| Job Category | Automation Risk | Jobs at Risk | Status |

| Customer Service Representatives | 80% | Millions globally | Already automating |

| Data Entry Clerks | 75% | 7.5 million by 2027 | High displacement |

| Retail Cashiers | 65% | Widespread | Ongoing transition |

| Telemarketers | 85-90% | High volume | Nearly obsolete |

| Bank Tellers | 25%+ decline | Significant | ATMs & mobile banking |

| Postal Service Clerks | 25%+ decline | Major reduction | Digital transformation |

| Job Category | Impact | Notes |

| Administrative Assistants | 40-50% | Routine tasks automated |

| Bookkeeping & Accounting Clerks | 45-55% | AI financial systems |

| Legal Assistants | 40-50% | Document automation |

| Manufacturing Workers | 40-60% | Robotics expansion |

| Transportation Workers | 30-50% | Autonomous vehicles (long-term) |

| Job Category | Impact | Notes |

| Computer Programmers | 30-40% | AI coding assistants |

| Proofreaders & Copy Editors | 35% | Generative AI tools |

| Credit Analysts | 30% | AI risk assessment |

| Graphic Designers | Declining demand | AI design tools |

| Job Category | Why Protected |

| Air Traffic Controllers | High-stakes decision making |

| Chief Executives | Strategic leadership |

| Radiologists | Complex medical judgment |

| Clergy/Religious Leaders | Human connection essential |

| Residential Advisors | Interpersonal care |

| Photographers (Creative) | Artistic vision |

| Position | Growth Rate | Demand |

| AI Specialists & Machine Learning Engineers | Very High | 350,000+ new positions globally |

| Data Analysts & Scientists | High | Top 3 fastest growing |

| Software & Application Developers | High | Continuous expansion |

| Information Security Analysts | High | Cybersecurity demand |

| UI/UX Designers | Moderate-High | Digital experience focus |

| Prompt Engineers | Emerging | New AI-era role |

| AI Ethics Officers | Emerging | Governance & compliance |

| Position | Growth Projection |

| Environmental Engineers | Top 15 fastest-growing |

| Renewable Energy Engineers | Rapid expansion |

| Sustainability Specialists | High demand |

| Energy Storage & Distribution | Growing sector |

| Position | New Jobs by 2030 | Driver |

| Farmworkers & Agricultural Laborers | 35 million | Green transition, food security |

| Delivery Drivers | Millions | E-commerce growth |

| Construction Workers | Millions | Infrastructure development |

| Nursing Professionals | High growth | Aging populations |

| Secondary School Teachers | Significant growth | Education expansion |

| Social Workers | Expanding | Care economy |

| Employment Type | Workforce | Percentage | Characteristics |

| Informal Employment | 25.95 million | 71.8% | Low security, variable wages |

| Formal Employment | 10.17 million | 28.2% | Benefits, social protection |

| Projected Formal (2030) | Growing | 38% | Gradual formalization |

| Factor | Current State | Challenge |

| Agricultural Workers | 28% of workforce | Mostly informal, vulnerable to automation |

| Small Businesses | 44% of informal economy | Limited AI awareness & resources |

| Unemployment Rate | 27% surveyed | High baseline vulnerability |

| Formal Job Awareness | 54% unaware of formalization programs | Education gap |

| Sector | Current State / Context | AI-Related Vulnerabilities / Threats | Emerging AI Use & Opportunities | Likely Impact |

| Agriculture (≈70% of Tanzanians engaged) | Backbone of the economy; largely manual and labor-intensive | • Automated irrigation systems • AI-powered pest detection • Precision farming reducing labor needs • Drone-based crop monitoring | • Smart agriculture solutions • Improved weather forecasting • Better market access • Productivity gains | Reduced demand for manual farm labor but higher efficiency and yields |

| Manufacturing & SMEs | Government promoting enterprise growth with digital tools | • Manual procurement processes • Labor-intensive assembly • Manual quality control | • Eva Docs.ai for procurement automation (local innovation) • Assembly line automation • Inventory management systems | Over 20+ hours/week saved in administrative work; fewer low-skill roles |

| Customer Service & Call Centers | Growing BPO sector in Tanzania | • AI chatbots replacing human agents • High exposure to automation | • AI-driven customer interaction tools | Immediate threat (2024–2025); up to 80% automation risk globally |

| Administrative & Clerical Work | Common across public sector, NGOs, and private firms | • Data entry automation • Bookkeeping software • AI document processing | • Digital record management • Workflow automation | Increasing job pressure as global AI standards expand |

| Financial Services | Expanding digital finance ecosystem | • Automated credit scoring • Risk assessment automation • AI-powered chatbots | • Fraud detection systems • Faster lending decisions | Reduced demand for entry-level finance professionals |

| Initiative | Description | Status |

| National AI Strategy | Comprehensive framework under development | Expected late 2025 |

| AI Research Lab | University of Dodoma & NM-AIST collaboration | Launched 2024 (Sh1.8 billion) |

| Digital Tanzania Project | Internet access, digital skills, government digitization | Ongoing |

| AI4D Agriculture Program | UN joint program (EU-funded, $3 million) | 2024-2027 |

| National Digital Education Guidelines | AI integration in education | Released 2025 |

| Barrier | Impact | Current State |

| Digital Infrastructure | Limited internet, unreliable electricity | Improving but inadequate |

| Skills Gap | Lack of AI professionals | Critical shortage |

| Awareness | 54% unaware of AI programs | Education needed |

| Regulatory Framework | No comprehensive AI oversight | Multiple agencies, fragmented |

| Investment | High costs for AI infrastructure | Limited funding |

| Period | Stage | Global / General Developments | Tanzania-Specific Context | Overall Implications |

| 2024–2025 | Immediate (Current Reality) | • Customer service automation (chatbots, virtual assistants) • Basic data entry elimination • Resume screening automation • Simple content generation • Retail self-checkout expansion • 76,440 jobs already eliminated in 2025 | • AI labs launching (e.g., University of Dodoma) • National AI strategy under development • Pilot AI projects in agriculture and healthcare • Limited disruption due to low AI adoption | Early signals of disruption; Tanzania still in a buffering phase |

| 2025–2027 | Acceleration | • Rapid expansion of administrative job displacement • Accounting and bookkeeping automation • Legal document processing by AI • Advanced customer service AI systems • Manufacturing robotics scaling • Major disruption timeline pulled forward to 2027–2028 | • Formal sector begins to feel AI pressure • Multinational firms introducing AI standards • Widening gap between AI-enabled and traditional firms • Early agricultural automation uptake | Productivity rises, but job insecurity increases in clerical and formal roles |

| 2027–2030 | Transformation | • Large-scale white-collar job restructuring • Transportation disruption (early autonomous vehicles) • AI integration in healthcare delivery • Education technology transformation • 30% of US jobs significantly changed (McKinsey) | • Formal employment projected to reach 38% • AI-skilled workers earn wage premiums • Shrinking traditional roles • Emergence of new tech-driven sectors • Growing rural-urban digital divide | Structural shift in labor markets and skills demand |

| Post-2030 | New Equilibrium | • New job categories firmly established • Human-AI collaboration becomes standard • Skills gap partially closed • Mature regulatory frameworks • Broader economic benefits realized | • More stable adaptation to AI • Stronger digital institutions • Improved alignment between education, skills, and labor demand | Long-term gains depend on policy, skills investment, and inclusion |

| Stakeholder | Timeframe / Focus | Key Recommendations | Expected Outcomes |

| Individuals | Immediate (2025) | • Pursue digital literacy training • Learn basic data analysis skills • Strengthen interpersonal and communication skills • Enroll in vocational training in growth sectors • Build an adaptability and lifelong-learning mindset | Improved employability and resilience to automation |

| Individuals | Medium-Term (2025–2027) | • Specialize in AI-resistant skills • Learn to work with AI tools rather than compete against them • Develop cross-disciplinary skills (tech + domain knowledge) • Network within tech and innovation communities • Explore entrepreneurship and self-employment | Higher income potential and smoother transition into emerging jobs |

| Businesses | Strategic Priorities | • Invest in employee reskilling and upskilling programs • Adopt AI gradually with human oversight • Partner with universities and training institutions • Prioritize ethical and responsible AI use • Prepare for hybrid human-AI workforce models | Productivity gains while minimizing workforce disruption |

| Government | Policy & Regulation | • Accelerate implementation of the National AI Strategy • Expand digital infrastructure (electricity and internet access) • Scale up funding for technical and vocational education • Establish regulatory sandboxes for AI testing • Strengthen social safety nets for displaced workers • Incentivize formalization using AI support tools • Implement rural-urban digital bridge programs • Prioritize women and youth due to higher vulnerability | Inclusive AI adoption and reduced inequality |

| Education Sector | Curriculum Reform | • Introduce AI literacy from secondary education • Teach coding and programming fundamentals • Expand data science and analytics training • Promote digital entrepreneurship • Embed human-centered design thinking • Teach ethics and responsible AI use | Future-ready workforce aligned with labor market needs |

Despite challenges, Tanzania has unique advantages:

| Country | AI Strategy Status | Key Focus |

| Kenya | Implemented | Agriculture, logistics |

| Rwanda | Advanced (Google partnership) | AI Research Centre |

| Nigeria | In education reform | Broad sectoral adoption |

| Tanzania | Developing | Deliberate, ethical approach |

Tanzania's Approach: Choosing deliberate, inclusive growth over rapid adoption may prove advantageous long-term.

Tanzania's Path Forward: The next five years will determine whether Tanzania becomes an AI winner or loser. Success requires:

The choice is clear: Adapt proactively or face displacement reactively. The AI revolution is not coming—it's already here.

Report Compiled: December 2025 Data Sources: Academic research, government reports, international organizations, and industry studies Geographic Focus: Tanzania with global context Time Horizon: 2025-2030